This is part two in a series about a mysterious suitcase that once belonged to a young Briton who followed his father into a career as a diplomat in the USSR in the 1930s. Check out parts one and three.

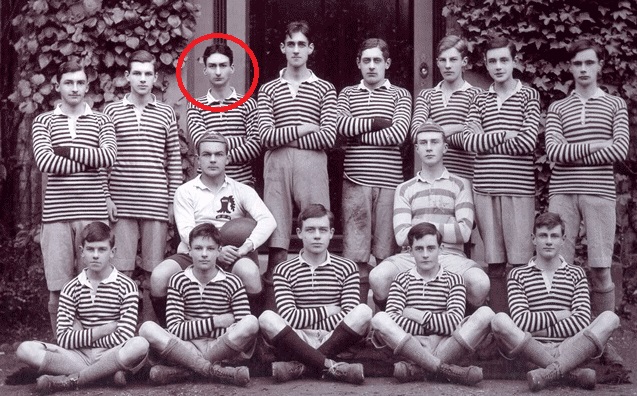

A school rugby team photo with the future Captain W.R. Frecheville of the Royal Engineers, whom the Bolsheviks would capture and execute in 1920.

Even as young George Walton was at Sedbergh, studying French, passing the ball on the rugby field, and bowling on the cricket pitch, he must have avidly followed his father’s career abroad. The Civil War was raging from 1918-1920. The U.K. deployed troops from the White Sea to the Sea of Japan.

In the south, where W.S. was stationed after he left Murmansk, the Royal Air Force flew combat missions against the Red Army. British ground troops and heavy Mark V and light Whippet tanks joined in the White attacks, Lauri Kopisto writes in a dissertation titled “The British Intervention in South Russia 1918-1920” (University of Helsinki, 2011). British tank crews led a successful assault on the Bolshevik stronghold of Tsaritsyn, later renamed Stalingrad. The Bolsheviks made clear their hatred for the foreigners, threatening to castrate and crucify any British prisoner of war who fell into their hands.

[Check out the new edition of The Insurrectionist.]

One morning as I sorted through my trove, a brownish scrap of paper fluttered out. Glued to it was a classified ad, evidently from the Times of London. I glanced over the paper, saw a date, and nearly stuffed it in a folder marked “1920s,” to investigate later. Yet something in the minuscule, eye-hurting font stayed my hand. I read:

ROSTOV, SOUTH RUSSIA.—INFORMATION WANTED about CAPTAIN W.R. FRECHEVILLE, ROYAL ENGINEERS, captured by the Bolsheviks near Rostov on January 8th or 9th, 1920, and reported to have been subsequently tortured and killed. Information also wanted concerning Lieutenant H. J. Couche, M.C. (Interpreter) Machine Gun Corps, who is believed to have been in Rostov at the same time. Parents will be grateful for reliable information.—Reply to Professor Frecheville, High Wykehurst, Ewhurst, Gilford.

Again, a mere scrap of writing suggested an entire novel. Evidently W.S. was looking into the disappearance of the POWs—whether from in Russia, Constantinople (where Britain had an occupying force after the Great War), or England itself. But who were these forgotten captives? I searched for Frecheville’s name and pulled up a remarkable exchange from the House of Commons on June 22, 1920.

Captain W.R. Frecheville

An M.P. named Mr. Leonard Lyle asked the Secretary of State for War, Winston Churchill, whether he had learned any further details concerning “the brutal murder by Bolsheviks of Captain W.R. Frecheville, Royal Engineers, and Lieutenant H.J. Couche, M.C., Machine Gun Corps.” Churchill replied that the Soviet government claimed to have no knowledge of the incident and “dismiss[ed] the story of capture and execution as an invention on the part of contra-revolutionary Russian newspapers.” However, Frecheville’s interpreter eventually escaped to Poland and confirmed his capture and murder, slain by sword blows to the head.

The photographs

One of the first things I discovered as I emptied the suitcase was a series of faded photographs. Boys in school ties lounging in a doorway. Eight men in suits posing before a train. A ship called the Danubian along a dock with stacks of lumber in the foreground. Maddeningly, none of the pictures is identified, but several of them likely depict George following his stint as a diplomat in Moscow from 1930-1934.

On a sunny day in the English countryside, he stands with his hands in his pockets. He wears spectacles and a jacket tightly fitted on his narrow shoulders, his baggy trousers hitched up to his navel in the style of the day. In his early thirties he wasn’t much taller than five-foot-six or so, his letters hint. With an overlarge head, protruding ears, and worry-furrowed forehead rising to a widow’s peak, his is not a face that projects confidence. Yet he was bold enough to throw aside his diplomatic career for the love of a woman. Also pictured are what may be his Russian mother and the wife he brought home from Moscow. In one picture, George lies supine in the grass while two women seated nearby smile. The younger woman touches the older on the shoulder with the casual ease of good friends. Snuffing about them is a Scottie dog.

Who were these people? Let’s rewind to 1920. Upon leaving Sedbergh, George attended St. John’s College, Cambridge, earning his B.A. in economics and law in 1923. There he met Malcolm Muggeridge, later a well-known author, satirist, and journalist. Upon graduation from Cambridge, George exchanged letters with officers of the 7th London Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, the chemodan reveals. When a commission failed to materialize, he served in various capacities from “office boy” to director at his father’s shipping company, according to a handwritten résumé he saved in the suitcase.

Late in 1930 George followed in his father’s footsteps into the Foreign Service, though W.S. had by now entered private life as the owner of a shipping company. George’s fluency in Russian made him a natural for Moscow. He arrived from Warsaw in the company of Lady Muriel Paget, he relates in a letter dated November 24. Paget was a philanthropist who had run a wartime Anglo-Russian hospital in Petrograd (Leningrad, in George’s day). She now planned to build a home for impoverished Britons stranded there. Many of these people were former tutors and nurses who had served aristocratic families—yet another potential novel embedded in a single line of a letter.

Nothing to eat but ‘bread and sunshine’

George’s letters home shed light on the diplomatic life in Stalinist Russia at a time when Moscow was a destination for a motley assortment of pilgrims to the New Jerusalem of the left. Writers, movie directors, foreign engineers, food faddists, free-love advocates, liberal clergymen, Red fellow travelers: they tended to be naïfs and dupes who showed up predisposed to view the monstrous Soviet experiment as a resounding success, as Muggeridge, who followed George to Russia, would portray them in his novel Winter in Moscow. Eventually George would cross paths with luminaries such as George Bernard Shaw—an admirer of Hitler and Stalin—and Shaw’s good friend, heavyweight boxing champ Gene Tunney, who unlike Shaw was clear-eyed in his recognition of Soviet totalitarianism. (As a Christian, Tunney was less inclined than Shaw to shrug off state destruction of churches and purges of believers.)

In his correspondence George used embassy stationery embossed with the rampant English lion and Scottish unicorn, along with the slogan Henry V carried at Agincourt: DIEU ET MON DROIT. George evidently jotted many of his epistles from his desk at the embassy. Apart from the letter which begins “My dear Londoners,” he almost always omitted the salutation. This comes across as brusque, disorienting. Was this simply an epistolary quirk, or did it perhaps allow him to array a Russian newspaper in front of him and pretend he was hard at work translating an article if a supervisor happened by?

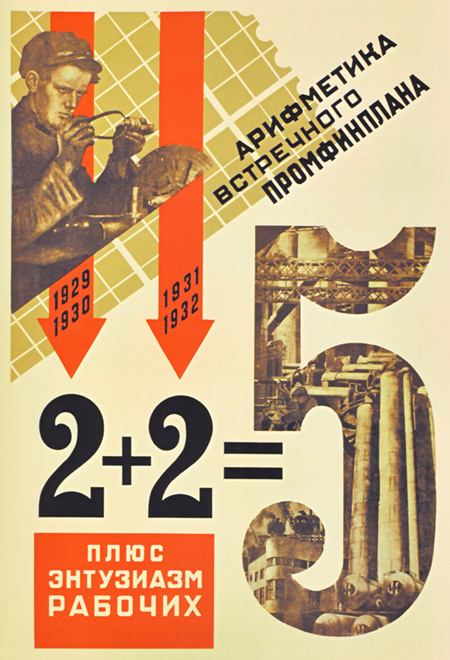

As one who had known prewar Moscow, George noticed the changes wrought by thirteen years of revolution, Civil War, and socialist economics. Holes pocked the sidewalk in place of the city’s former shade trees, likely cut down to provide firewood. Propaganda posters and placards covered the walls. George notes one slogan—FIVE-YEAR PLAN IN FOUR YEARS—which was sometimes depicted in graphic shorthand as 2+2 = 5, inspiring Orwell’s notorious equation of totalitarian mind control in 1984. Across from the Duma building was a model of a dirigible bearing the name of the newspaper Pravda.

Rations were so small, people survived on “bread and sunshine,” George says. “There’s nothing to eat; no horse[s], no shoes; workers get everything according to the distribution list.” Workers were guaranteed a salary of 100 rubles a month but had few places to spend their earnings in an economy where basic goods were scarce and unaffordable. Butter cost 30 rubles a kilo, and street vendors sold only poor-quality apples, cucumbers, and sausage. Consequently, hungry members of the new proletariat were blowing their salaries on face massages at 10-15 rubles apiece. The British consul to Leningrad submitted to his Soviet hosts a long list of goods he was unable to find in the inefficient socialist economy, among them a corkscrew and a broom, George writes. In response he received only a broom handle.

By the way [George adds] Moscow has got a peculiar and not very pleasant smell. Unwashed humanity plus something that I can’t place. It’s the same everywhere, except in the part of the house in which we live: in shops, in telegraphs, in hotels, and if you pass an open door the same smell comes out and hits you. When I return I suppose all my things will have to be fumigated to get rid of it. I am gradually getting used to it now.

Perfect Russian

George’s fluency in Russian quickly won his superiors’ praise. In a dispatch to London, the ambassador, Sir Esmond Ovey, describes traveling in Ukraine with his staff interpreter. “I am much indebted to Mr. Walton whose complete knowledge of the vernacular enabled him to understand every word said to us irrespective of the noise of trains, steam hammers, or local variety of accent,” Ovey wrote. (The letter is preserved in The Foreign Office and the Famine: British Documents on Ukraine and the Great Famine of 1932-1933, edited by Marco Carynnyk et al, p. 11.)

George settled into the life of a minor princeling in Moscow’s diplomatic elite. He attended parties and concerts, learned to ice-skate on a flooded tennis court. The city was not all that was fragrant; George had to resign himself to weekly baths, as hot water was delivered only on Saturdays. He complains that his salary is no better than that of a receptionist. A later job application letter claims he was earning ₤650 a year by the time he left Russia, but that might have been an exaggeration to boost his pay prospects in his next position.

To augment his take-home, he proposed a series of business schemes. One of them illustrates the absurd inefficiencies of Soviet economics. George wanted to import a Cyrillic typewriter from England, then sell it in Russia, where they were hard to come by. Elsewhere, he begs his parents to wire cash to buy a diamond, which he says he can resell abroad for double the asking price. He proposes buying rubles from a bank in Harbin, and selling them to his own embassy in Moscow. This was because he could get an exchange of 500 rubles to the pound in Harbin, compared to the official rate of 249 in Russia. In one bag he sends his family an early Makovski painting. “There are quite a number of pictures for sale here—a couple of pounds or even less, and by well-known artists—Vasnestov, Vrubel, etc., but somehow none of the subjects are very good,” George writes in September 1933.

Politically, George’s beliefs appear to be a grab bag. In November 1931 he writes that the embassy staff in Moscow held an election night party celebrating a Conservative coalition’s landslide victory. “Everybody was awfully pleased by the results,” George writes. Yet he was open to the Bolshevik experiment upon his arrival in 1930:

Here are these people trying to do their best. They may be misguided and things are done in a strange manner, but let’s be absolutely fair and give them a chance to show what they can do. Things on the whole seem to be much better on the surface than we realized in England. … [T]he five-year plan seems to be working to a certain extent. They can produce all the goods at very low prices as the actual cost of production is nearly equal to the barter value of the rations. … So they can dump in any country they care to do so.

Nevertheless, George caught glimpses of the fear at the heart of Stalin’s Russia. “You see people walking and talking in the street, when you come near they stop talking,” he writes. Days after his arrival, George, accompanied by the wife of a colleague, was dispatched to observe a show trial of Professor Leonid Ramzin. Arrests of such so-called “wreckers” were commonplace in the Soviet Union as Stalin sought to assign blame for the government’s failed economic policies. While heading there in an embassy car, George and Mrs. Paton pair got caught in a government-organized demonstration.

‘The dirty swine started applauding’

Soldiers guard the defendants at a Soviet show trial, 1930s.

The Outlook and Independent reported Dec. 10, “The Soviet government came forward like a veritable [P.T.] Barnum,” beginning with “a be-bannered demonstration of 500,000 people tangling Moscow’s traffic and crying death to the traitors, foreign imperialists and oil kings.”

Guarded by soldiers in peaked helmets and with fixed bayonets, the defendants—economists and engineers accused of treason—blinked beneath thirteen arc lights set up for the cameras. Their “waxed faces [were] stoical before a battery of microphones which carried their words across the country,” The Outlook and Independent reported. The charges were absurd on the face of it: undermining the socialist economy and creating an anti-Soviet Industrial Party, along with a parallel, 200,000-strong peasant party. The accused confessed to conspiring with a French agent named Monsieur R. and with Britain’s Lawrence of Arabia.

In a November 26 story, The New York Times’ Duranty served as Stalin’s mouthpiece, sneering at one of the doomed defendants as “a long, thin, undulating worm of a man with a small black head.” Duranty’s editors at the Times were happy to publish an account that quoted nobody but state-appointed sources (including the self-accusing defendants). Yet even Duranty noticed the oddity of the spectacle. He noted the eager confession of lead defendant Leonid Ramzin, a leading specialist in heat engineering and boiler construction:

MOSCOW, Nov. 26.—“Why have a prosecutor at all?” was the whispered comment of a Soviet reporter as Professor L.K. Ramsin [sic], on trial for plotting against the Soviet and whose voice had risen clear and strong in seven hours of self-denunciation, ended his testimony against himself today.

“Thus we planned and worked to sow discouragement and produce a crisis in the Soviet land,” Professor Ramsin said, “to prepare intervention by foreign foes, to restore the capitalists and landlords and to plunge the country afresh into a bloody war. In these plans and this work the central role was played by me—I admit it.”

On December 9 George was back at the trial, this time accompanied by Lady Muriel Paget, who had shown up at his quarters and awakened him that morning. Unlike Duranty, George recognized that the trial was staged like a play. He saved his admissions ticket, writing on the back, in Russian, the names of each of the eight defendants and his sentence:

Ramsin: death

Feoorov “

Larichev ”

Etc.

“When the dirty swine started applauding after the sentence had been read,” George writes, “I felt really sick—bread and circuses.”

It appears from George’s notes that the sentences may have been commuted to eight or ten years, depending on the individual, but Ambassador Ovey was pessimistic about the defendants’ fate.

“On my return the ambassador asked me my opinions and I described what I had seen,” George writes. “He told me that 6 of the 8 will be shot.”

(In fact Ramzin’s sentence was later commuted, both because he eagerly served as a star witness at a later trial and because of his essential skills. This dire enemy of the state would go on to win an Order of Lenin and a Stalin Prize.)

A traveling dead man

Despite the terror of the times, George’s cultural fluency caused Russians to forget he was an Englishman. In a dispatch to London after a trip through Ukraine in May 1932, Ovey noted that passengers are chary of chatting with foreigners, due to the presence of the feared secret police known by the acronym GPU or OPGU. “These officials travel untiringly back and forth like the birds on the Bosphorous—the unquiet souls not of dead dragomans but as living and active representatives of an all-pervading Okhrana,” Ovey writes, referring to the tsarist secret police.

Sir Esmond Ovey, British ambassador to the Soviet Union, looks a tad wobbly on skates.

Yet when George was assigned to ride in a separate carriage with GPU agents, the agents let down their guard.

Much of the conversation, he informed me, was of a general character about various colleagues and their adventures on the road [Ovey writes]. In one case one of them so far forgot himself as to state that one of his friends had been to a place in the Polesie district, presumably a village, where the men had literally nothing but their shirts to walk about in. He was, however, recalled to a sense of his responsibilities by his colleagues, and no further admissions of this kind were made.

Was a vodka bottle circulating, or was the agent lulled to incautiousness by the Englishman’s perfect Russian and a camaraderie formed over the clattering hours in a four-berth train cabin? One can imagine the fear that slunk over the agent’s face as he realized his error. He knew his colleagues would report him to their supervisor. They had to. Of course, poverty like that, the Party’s already vanquishing it, he might have added, seeking forgiveness in his comrades’ hard eyes. Unlike you capitalists, George, with your Great Depression.

Too late. He was already a traveling dead man, left only to wonder whether he would be arrested in route, upon arrival at Moscow’s Kievsky station, or in his own apartment before his wife and children.

To be continued…