This is the first in a three-part series. Check here for parts two and three.

I knelt packing my bag on the floor of the London townhouse of Andrew Fox, a British businessman and friend from when we both lived in the Russian Pacific seaport of Vladivostok. I had come here to interview him for a memoir piece on the 1990s and early 2000s in Russia’s “Wild East.” This was a turbulent era when mob-linked political bosses kidnapped journalists, a shipping industry whistleblower was blown to bits by TNT planted under her bed, and the governor threatened to jail Andrew, who also happens to be the honorary British consul general to the city.

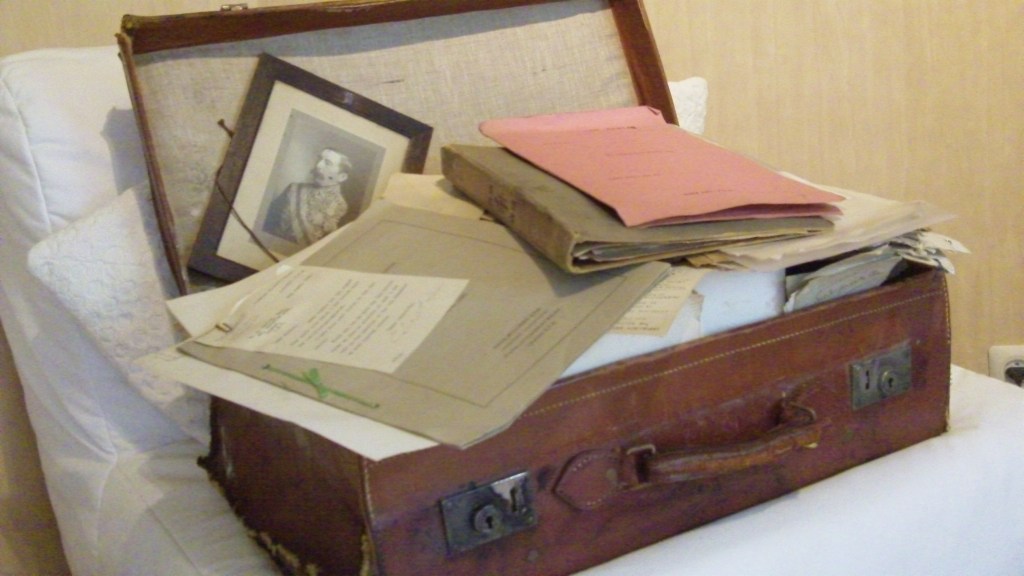

I was double-checking my passport, wallet, and other essentials (My hearing aids! Oh, in my ears) when Andrew came thumping downstairs with a leather suitcase. As scuffed as old shoes, it was peeling open and dusted with dried mold that rubbed off like chalk on one’s clothes.

Unidentified photograph found in the suitcase, likely of George Walton, his wife Natalia (Tata), and his Russian mother.

“Before you go, did you want to take a look at this?” he said.

That’s right; he had mentioned something about a suitcase full of old British documents concerning Russia. I was heading to St Pancras to catch a train back to Belgium. Yet who could resist this strange object? “Suitcase” translates as chemodan in Russian, a word as ordinary as its English equivalent. But when applied to this curiosity, it seemed to describe a magical object that might pop up in an Isaac Bashevis Singer story.

“Sure,” I said. “We have time.”

Andrew snapped open the locks and raised the lid. The suitcase was stuffed with hundreds of yellowed documents, as well as a framed photograph of a walrus-mustached chap in a gold-braided uniform befitting a Latin American generalissimo. Among the papers were letters handwritten on stationery that read:

BRITISH EMBASSY,

MOSCOW

[Check out Russell’s novel, The Insurrectionist.]

On the first page someone had written in a crimped hand, “2 December 1930.” Below that it began, “My dear Londoners.” It was a diplomat’s letter home.

“Where did you get this?” I said.

“Oh, a guy approached me at the time of my troubles with the governor. He’d heard an interview with me, and wanted to sell me the suitcase. There’s a lot of material on the Far East that he thought might interest me. Take it if you want. Maybe you’ll find a story in here.”

Sorting out history

That evening I began sorting out the contents in my studio at Villa Hellebosch, a thatched-roof country manor which was then a retreat center for writers sponsored by the Belgian literary organization Passa Porta. The papers were mostly in English but included some in Russian. They spanned at least thirty years, beginning with a tsarist-era war bond from 1915. Soon I set aside the project I had been working on, and devoted the rest of my fellowship to the chemodan.

At first all I knew was what Andrew had told me: the suitcase had belonged to a long-dead diplomat named William George Walton, who had served in the British embassy in Stalin’s Soviet Union from 1930-34. Andrew had bought the suitcase from Warner Dailey, an English antiques dealer who had unearthed it in a weekly “country market”—a sort of flea market—on the Kempton Park racecourse near London. The sellers are often people who buy up estate sale leftovers. Dailey had been interested in Russia since boyhood, when he took a course from an elderly White Russian. Whenever he visited the market, he later told me by phone, he would call out, “Got anything from Russia?” One day in the late 1990s, a seller working from the back of a station wagon offered him a look at the suitcase.

“I saw there was stuff to do with Vladivostok,” Dailey said, “and a lot which appeared to be about the White Russian struggle against the Bolsheviks in various parts of the country.”

Dailey forked over ₤200, and the chemodan was his. He learned about Andrew amid media coverage of the governor’s threat. Dailey looked up Andrew and sold him the suitcase. And now I was its custodian.

As I spread out hundreds of pages on the floor, the mysterious chemodan transported me across more than a century of history. It was bigger inside than out, containing lost worlds. Sometimes it seemed that every slip of paper I found suggested the plot of a full novel. So who was this forgotten diplomat and amateur archivist?

For one thing, he was a packrat. Along with the documents of obvious historical value, there were old shipping cargo manifests; notes acknowledging a series of ₤10 checks sent by the Rhodesia-Katanga Junction Railway and Mineral Co. on behalf of a Russian in Kazakhstan; a receipt for a shirt, two collars, socks, and suspenders from an outfitter in Cambridge; and a weekly menu from the Moscow Embassy canteen. (Monday breakfast: “Porridge. Bacon. Apricot jam.” Lunch: “Corned beef. Potatoes, haricots. Rice pudding.” Dinner: “Fish cake. Chips.”)

More interestingly, there were letters referring to the Bolsheviks use of stolen British embassy plates at a banquet for diplomats in 1931, to the toady foreign correspondents who sang Stalin’s praises as his henchmen killed millions, and to a poet named Sergei Yesenin who wrote his last lines in blood and hanged himself. I found an invitation to a reunion dinner for veterans of the British Expeditionary Force to the Arctic seaport of Murmansk in May 1918. Tucked in one folder was a 1917 report by the Kerensky government on Grigori Rasputin, a mystic favored by the late Empress Alexandra. Dozens of pages illuminated the Russian Civil War in Siberia and the Far East, including eyewitness accounts of the Bolshevik razing of a Far Eastern town in 1920.

And inevitably, where humans are involved, there was love. Amid mass arrests, when it was dangerous for ordinary Soviet citizens even to speak to foreigners, an English diplomat in Moscow fell in love with a Russian woman said to be a member of a famed aristocratic family.

Father and son diplomats

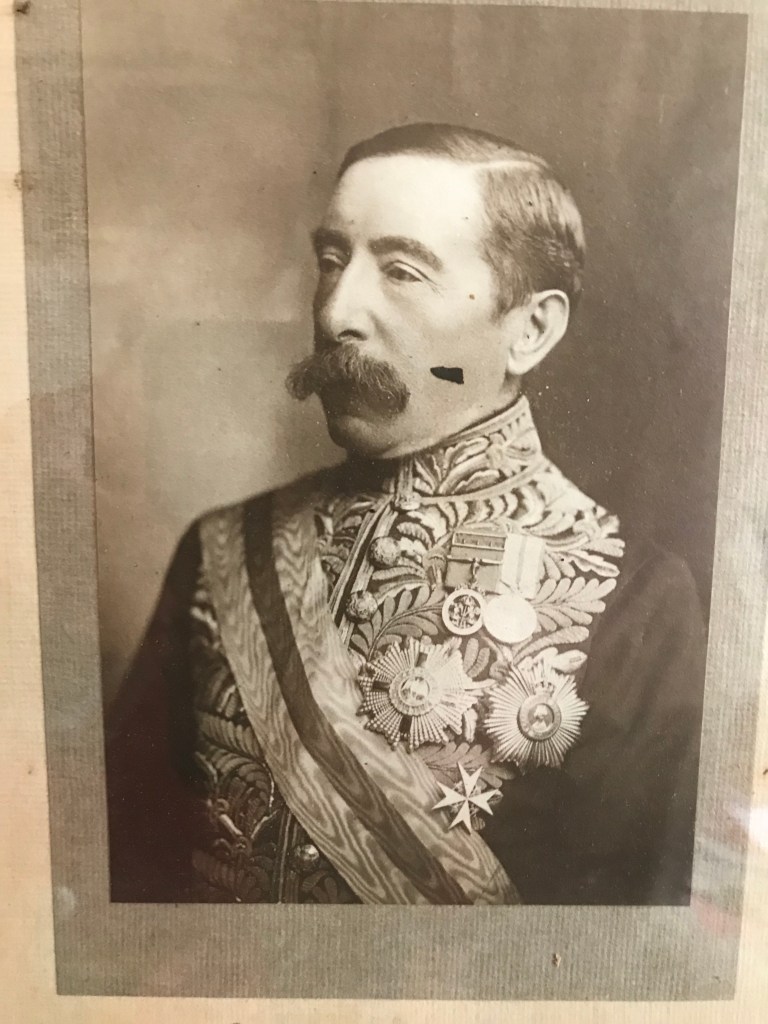

A framed portrait of Henry Stafford Northcote, first baron Northcote, was saved in the suitcase for unknown reasons.

As I pieced through the chemodan, I discovered its contents were the work of not one but two William Waltons: a father and son whose diplomatic careers in Russia spanned half a century beginning in the 1880s. William Sherrington Walton, who used the initials W.S., served as a consular official in several assignments across Russia and Ukraine. His son William George Walton (who went by George) was a third secretary and translator in the British Embassy in Moscow in the thirties.

Though W.S.’s early life is unknown, he held a series of posts in the Russian Empire beginning in 1884, representing Britain’s interests in Taganrog, Mariupol, and Rostov-on-Don, the U.K. Foreign Office confirms. His wife, Maria, was Russian, though how and where they met appear to be lost to time. Evidently they had memorable dinner at le Restaurant de la Réserve in Marseille Sept. 7, 1907; they saved the menu in the chemodan.

Before the Revolution much of his work was commercial in nature. In an 1899 report from the southern Russian seaport of Mariupol, W.S. wrote several thousand words on nearly every aspect of the economy, among them shipping, cereals, pig iron, coal and agriculture. “The winter of 1899-1900 has been very severe, and it is fully expected that owing to the absence of snow … the winter crops may have suffered.” Elsewhere, he warned that British tool and machinery manufacturers were being underpriced by Americans, even though the Yanks had higher transportation costs. A letter from the Foreign Office in 1919 reveals that he was earning a salary of ₤400 a year, along with a 33% conflict bonus because Russia was embroiled in Civil War.

One day after a miles-long walk through fields stinking of manure, after a beer in a tiny country tavern where farmers puzzled over the presence of a foreigner who did not understand their questions in Flemish, I returned to Villa Hellebosch to discover a document that seems to cast light on George’s childhood.

George was born February 13, 1902, a year in which his father was serving as a consular officer in Taganrog on the Sea of Azov. But an unsigned document in George’s handwriting, titled “Childhood,” describes an idyllic youth in the Caucasus Mountains. Perhaps it is the start of a never-realized memoir. An alternative, that it is a fragment of a novel or short story, seems less likely to me, but the reader is free to draw that conclusion. Either way, it indicates a familiarity with the Caucasus. Let’s stipulate for narrative ease that it was a memoir.

If so, George’s father was consumptive, and for his health the family lived for a time in a village in the Caucasus, an iconic landscape in Russia’s literary imagination. The troubled southern frontier is the setting of works such as Pushkin’s “The Prisoner of the Caucasus,” Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time, and Tolstoy’s Khadzhi-Murat.

The bear in the garden

When George was five, his sister was born; later, from Moscow, he would correspond with a sister named Eda. The memoir states, “I remember mother calling me into her room, placing me on her bed, and letting me hold something small and vociferous, which I at once christened ‘Lialka’” (an endearment for baby). The countryside surrounding the Waltons’ property was wild and picturesque. On clear days the mountains seemed to rise out of the family’s small estate and orchard. Every schoolchild in Russia can recite Pushkin from memory, and George was surely familiar with his seminal works such as “Caucasus,” explored here by a translator in a blog for Ocaso Press:

Around me loom the Caucasus: a constant view

of snow-draped cliffs and slopes, where now my eyes

pick out an eagle, solitary, whose distant rise

will leave it motionless…

George and Lialka established a “zoo” in the garden, adopting a fox and twin bear cubs their father brought home after a hunt. The bears were allowed the run of the property. One of them strayed and drowned in a river, but the other began making mischief. One day it climbed into the children’s nurse’s kiot, or icon closet, and drank the holy water she kept there.

“After this sacrilegious crime, which was the culmination of a series of secular ones, he was kept in a cage,” George writes.

Over the protests of his sobbing children, W.S. tried to dump the bear in the woods. But as the family drove off in their carriage, the cub ran after them, “crying for all he was worth.” Doubtless with a sigh of parental defeat, W.S. tugged on the reins, hauled the bruin onboard, and carried it back home. He later dropped it off far away in the woods—this time without the children.

George continued his schooling in England, even as his father represented the crown in Russia during the Civil War. In 1918, while George was enrolled at the elite Sedbergh School in the Yorkshire Dales, W.S. was posted to Murmansk with a British Expeditionary Force sent by Winston Churchill, then minister of munitions, in an attempt to contain the Russian revolution.

Civil War across Eurasia

By 1920 the elder Walton was honorary consul in Kharkov, Ukraine, where he helped fleeing British expatriates and anti-Bolshevik Russians as Civil War swept a nation larger than the entirety of South America. The chemodan contains a surprising number of documents concerning places where neither W.S. nor George ever served, in Siberia, the Russian Far East, and the Russian-dominated city of Harbin, China. (My wife Nonna and I have been lived in the Far East and have visited Harbin, where an onion-domed Orthodox cathedral, now a museum, stands in the center of town.) One typed document, dated May 19, 1920, is titled “Conversation with Gen. Ivanov-Rinov,” a White commander known for barbarities and slaughter in Siberia. The general said that the Bolsheviks cut him off west of Krasnoyarsk, so he escaped disguised as a peasant. Over several months, he made his way 1,300 miles east to the Whites’ Siberian headquarters in Chita.

As the Whites collapsed across the southern front, W.S.’s hands were full. He compiled lists of British subjects evacuating the country. A note from a fellow diplomat requests help for a member of the late tsar’s entourage escaping Russia in 1920. (“He has been useful to us from an intelligence point of view.”) After W.S. returned to London, an Englishman named Charles Blakely wrote to ask for support in a request for compensation from the British government, noting that W.S. was familiar with the situation. Blakely complains that his house in Kharkov was requisitioned for use by a White general, “that drunkard [Vladimir] May-Mayevsky, with the full knowledge and approval of the British Military Mission.”

Blakely adds bitterly:

On the British Mission quitting the town, leaving the house without any supervision or occupants, since they had turned out my dvornik [janitor] and my family to make room for their servants, the Bolshevik mob not only looted the place but smashed up doors and windows. No other house in the town was destroyed, and in this isolated case the reason was the house was being regarded as the British Military Headquarter.

He later dropped a note to thank W.S. for writing to the government on his behalf.

§

Spring of 2014 was a fitting time to receive a suitcase stuffed with history. That summer was the hundredth anniversary of the outbreak of World War I, and I was staying on Flemish soil that had been occupied by Imperial Germany. Crimea, once W.S.’s turf, was in turmoil as Putin sent troops to seize the peninsula from Ukraine. Villa Hellebosch was an unusual fellowship in that only two residents were present at a time, in addition to the owner of the estate and a cook. The other writer was an Estonian named Eeva Park, and Russia’s aggressions in the Black Sea had caused her to suffer a crippling writer’s block. She worried that Vladimir Putin, who has often lamented the breakup of the Soviet Union, would also invade her homeland on the Baltics. She spent hours on the internet every day, devouring news accounts of the Crimean crisis. Because my wife is Russian and I had lived in Vladivostok, Eeva and I had found common ground discussing current events.

After I returned from my weekend in London, my reports on what I found in the chemodan always set off our dinner conversations when we emerged from our studios. Often the homeowner joined us, and one night a group of Belgian writers came to dine.

As we filled our wine glasses, Eeva would ask, “How’s George?”

“You’re not going to believe what I found.”

“Tell me.”

“You know Walter Duranty, The New York Times correspondent who covered up the Ukrainian famine?”

“Of course.”

“George tried to help him buy a yacht in the Aegean. He and his father were in the shipping business in the twenties and thirties.”

Two hours later, we would tear ourselves away from the conversation to return to our writing studios, and I spent my evenings trying to make sense of the chemodan’s avalanche of documents, of stories.

To be continued…