Riots—and even gunplay—often followed circuses as their showgrounds drew drunks, toughs, and rowdy college boys. And the troupers brawled to defend the show.

Part one of two.

By Russell Working

WHEN THE O’BRIEN CIRCUS set up in Scranton, Pennsylvania, more than a century ago, performers and roustabouts alike sat down to eat in their new cook tent.

The tent walls were open, and as the troupers tucked into a dinner of meat and vegetables dished from giant kettles, they noticed they were surrounded by a throng of sullen men. The towners were miners, black-faced with coal dust and still wearing their lantern helmets from work.

The miners began lobbing rocks at the kinkers, knocking over several cook pots, lion tamer George Conklin recalls in his 1921 memoir, The Ways of the Circus. When the circus owner stepped out to calm the rowdies, a stone laid him flat, Conklin writes.

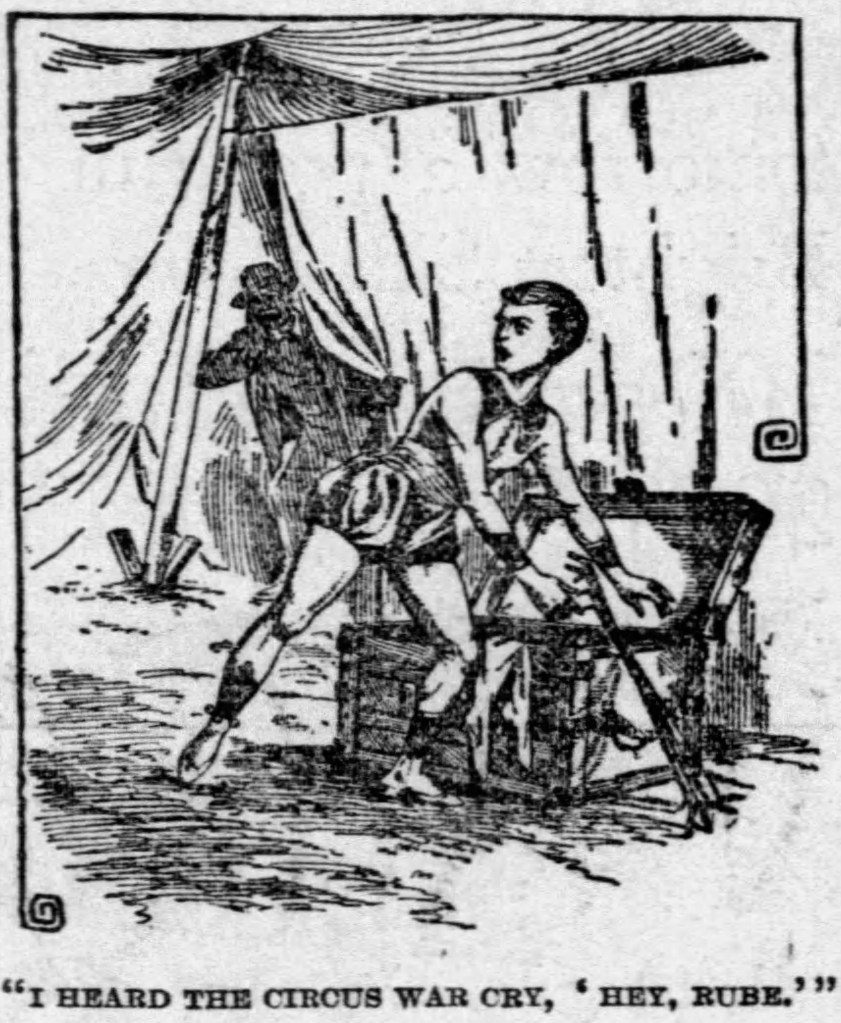

An O’Brien man screamed, “Hey, Rube,” and the troupers stormed out of the tent to meet their foe in a melee.

For decades, “Hey, Rube” was the battle cry that brought circus men running from across the showgrounds for a Donnybrook against towners, whom the circus folk often called “rubes.” The Oxford English Dictionary dates the phrase to 1882, though earlier references abound. The Cincinnati Daily Enquirer defined it in 1878 as “the rallying-cry of war for every employe [sic] of the show.” (Circus folk also called the fights “clems.”)

In a 2011 article for Humanities, Daniel Noonan cites David Carlyon, author of the book, Dan Rice: The Most Famous Man You’ve Never Heard Of.

Favorite sport

“Violence was one of America’s favorite sports,” Carlyon writes, and the circus was one of its favorite venues. Local ruffians waited to stew up trouble in each new town as eyes looked on with suspicion and excitement. There was gambling outside the tents and plenty of alcohol. It was rare if there was a show without a fight. “A circus had to be,” says Carlyon, in the words of one circus veteran, “an efficient fighting unit.” Performers were hired for their talent, but also for their ability to brawl. One extreme incident was the Hippodrome War in 1853, in which a circus outfit was unable to leave Somerset, Ohio, for two days because of ongoing fighting with locals. Many people were seriously injured and some killed.

A shout of “hey, Rube” always sent a cold shiver down the back of W.C. Coup, manager of the O’Brien circus. The shouted words immediately brought together hundreds of men armed with stakes and clubs, he told the Boston Daily Globe in May 1883.

“[B]ut stakes and clubs,” he said, “are terrible weapons in the hands of such men, all wild with excitement, and ready for a desperate and pitiless fight… You have to fight for your lives, and stand by one another, or be killed.”

The brawls could be deadly. In LaSalle, Illinois, a ferocious battle left several men dead on both sides, he said. A mob in Toronto overpowered a circus and burned all its tents and wagons. A pitched battle led to a fatality in Columbus, Indiana, on July 13, 1891, the Chicago Tribune reported.

Mere boys sometimes attacked the circus in organized gangs, trying to get into the show free. A mob of fifty South Side delinquents stormed a Chicago circus June 12, 1900, the Tribune reported. They came armed with knives, and several slashed their way through the canvas. The circusmen cried, “Hey, Rube,” and the fight was on.

Bernard Orton, a tightrope walker, clobbered a young tough named James Houlihan over the head, knocking him senseless. Both were arrested. Orton paid a fine of $50, and Houlihan was packed off to juvenile court.

Chicago mob cuts the tent ropes

In another Chicago melee, the Tribune reported May 11, 1895, a small boy sneaked under the tent, only to be met by a burly showman, who punched the child in the face. A swarm of 500 angry circusgoers attacked the show as shouts of “hey, Rube!” went up. Cops tried to break up the battle. The towners cut the tent robes, causing the big top to flap wildly about as a thunderstorm and torrential rains descended.

“A heavy gust of wind lifted the big canvas and it flapped ominously,” the Trib reported. “The policemen and employes [sic] made a rush for their lives.”

The canvas collapsed on several of them, but no one was seriously injured.

A retired circus man named W. E. “Doc” Van Alstine recalled his show days in a 1938 interview with a writer for the Work Projects Administration. His worst “hey, Rube” occurred in Lincoln, Illinois:

The town boys was coalminers and some of the toughest customers I ever seen. We strung out in a circle around our stuff and stood ’em off with “laying out pins” and whacked ’em with “side-poles”, finally giving ’em the run, but they sure could take it.

Another “Hey, Rube” in Ann Arbor, Michigan, was started by a gang of students from the University of Michigan, for no good reason at all except perhaps they thought it was funny. It cost the circus I was with more than $35,000 in lawsuits and damage to equipment. In a “Hey Rube,” most of the lawsuits that follow is usually by some innocent bystander who gets hurt in the scramble.

Coming: Dixie pride sparks ‘hey, Rube’ circus brawls.

For more about my novel manuscript, The Elephant Box, click here. Why a circus blog? Learn more here.

So interesting! Thank you. Circus is so much fun.

Very sad that the one place we had to be close to these magnificent creatures was hated so much by the low class thugs. And now our elite snobs who act like the ruffians of old, think they know what is best for all animals like PETA have essentially run them out of town on a rail. Burk

Yes, sad either way.

Pingback: Dixie pride sparked ‘hey, Rube’ circus brawls | The Elephant Box • A Circus Blog